Answering a speaking request from the Nebraska Natural Resource Districts, I delivered a talk last week in Central Nebraska. Kearney, Nebraska to be more exact. Kearney is located deep into the irrigated area of the Great Plains, and so I wondered a little – actually more than a little – why this group would be interested in my focus area of soil erosion. More specifically, why they would be interested in hearing about our Iowa State University project called, The Daily Erosion Project.

Continue readingEagle Grove Students Learn about Conservation Practices on the Farm

Eagle Grove, IA – On September 20th, the Earth Science class from the Eagle Grove High School took a field trip to a farm operated by Tim Smith. Smith, a White House Champion of Change for Sustainable and Climate-Smart Agriculture, showed how he incorporates cover crops, strip tillage, and a bioreactor into his farm operation. Students also traveled 12 miles north of his farm to tour a wetland CREP site. Tim, along with Bruce Voigts and Tas Stephen from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in the Clarion USDA office, discussed how the benefits these practices add to soil health and water quality.

Continue readingPartnering with States to Cut Nutrient Pollution

By Joel Beauvais; originally posted on EPA Connect, the Official Blog of the EPA Leadership.

Nutrient pollution remains one of America’s most widespread and costly environmental and public health challenges, threatening the prosperity and quality of life of communities across the nation. Over the last 50 years, the amount of excess nitrogen and phosphorus in our waterways has steadily increased, impacting water quality, feeding harmful algal blooms, and affecting drinking water sources. From the Lake Erie algae blooms to the Gulf of Mexico dead zone, nutrient pollution is impacting every corner of our country and economy.

In 2011, EPA urged a renewed emphasis on partnering with the states and key stakeholders to accelerate the reduction of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution through state nutrient load reduction frameworks that included taking action in priority watersheds while developing long-term measures to require nutrient reductions from both point and non-point sources. Many states and communities have stepped up and taken action, supported with EPA financial and technical assistance. States have worked with partners to reduce excess nutrients and achieve state water quality standards in over 60 waterways, leaving nearly 80,000 acres of lakes and ponds and more than 900 miles of rivers and streams cleaner and healthier. And, in the Chesapeake Bay region, more than 470 wastewater treatment plants have reduced their discharges of nitrogen by 57 percent and phosphorus discharges by 75 percent.

We’ve made good progress but this growing challenge demands all hands on deck nationwide. Recent events such as the algae bloom in the St. Lucie Estuary in Florida and high nitrate levels in drinking water in Ohio and Wisconsin tell us we need to do more and do it now.

That’s why I signed a memorandum that asks states to intensify their efforts on making sustained progress on reducing nutrient pollution. EPA will continue to support states with financial and technical assistance as they work with their local agricultural community, watershed protection groups, water utilities, landowners, and municipalities to develop nutrient reduction strategies tailored to their unique set of challenges and opportunities. Partnerships with USDA and the private sector – for example the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) projects in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and more efficient fertilizer use on sensitive lands such as in the Maumee River basin in Ohio – are yielding more rapid nutrient reductions in areas most susceptible to the effects of nutrient pollution. Private sector partnerships that engage the power of the food supply chain, such as the Midwest Row Crop Collaborative Exit, hold much promise too. Innovative permitting solutions are driving improvements. For example, Boise, Idaho’s wastewater treatment plant permit that allows them to meet their nutrient limits in part by treating and reducing phosphorus in agricultural return flow in the nearby Dixie Drain at less cost to the taxpayers. These examples and others show us that states, in cooperation with federal agencies and the private sector, can drive nutrient reduction actions.

To help states make further immediate progress, this year EPA will provide an additional $600,000 of support for states and tribal nutrient reduction projects that promise near-term, measurable nutrient load reductions. This assistance will focus on public health threats from nitrate pollution in drinking water sources and harmful algal blooms in recreational waters and reservoirs.

With continued collaboration and partnership, I am confident we will make greater and quicker progress on achieving significant and measurable near-term reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. In turn, we will support a more vibrant economy and improve public health for all.

Read more about EPA efforts to reduce nutrient pollution.

Iowa’s Water Crisis: Let’s Talk

We have all come to realize from the recent discourse in the news that water quality can be a bit political. Academic types, like myself, prefer to avoid situations where the political nature of controversial issues are likely to erupt. Last week, the Story County Iowa Democrats hosted a public discussion titled, “Iowa’s Water Crisis: Let’s Talk” in Ames, Iowa. I was invited to be part of the panel discussion alongside Bill Stowe, CEO of Des Moines Water Works, and Seth Watkins, a farmer and Republican from Southwest Iowa. During this event, we had the ‘opportunity’ to objectively discuss Iowa’s water crisis.

Continue readingA Weekend of Algae

Over September 9-13, our new ISU PhD student Tania Leung and I traveled to northwest Iowa to the Lakeside Laboratory. Our goals at Lakeside were twofold: to collect preliminary data on our Iowa Water Center funded project in order to plan our field campaign for summer 2017, and

to participate in the Phycological Research Consortium (PRC).

Farmers Connect Conservation to Water Quality at Big Spring

Elkader, IA. – On August 10th, fifty farmers from the Upper Roberts and Silver Creek Watersheds enjoyed an evening of family fun at the Big Spring Trout Hatchery along the Turkey River near Elkader. The Second Annual Landowner Appreciation Day allowed farmers and their families to follow the path of water that drains from their land to where it reemerges at Big Spring.

Continue readingWhen it comes to water…

From Melissa Miller, Iowa Water Center Associate Director

What a difference a week makes. Last Friday, my family and I made a lunch and relaxation stop in Elkader on our way to Wisconsin for a weekend getaway. My girls love water, so we walked over the Keystone Bridge for a good look.

Hana, 3, and May, 5 pose near the Turkey River in Elkader on 8/19/16.

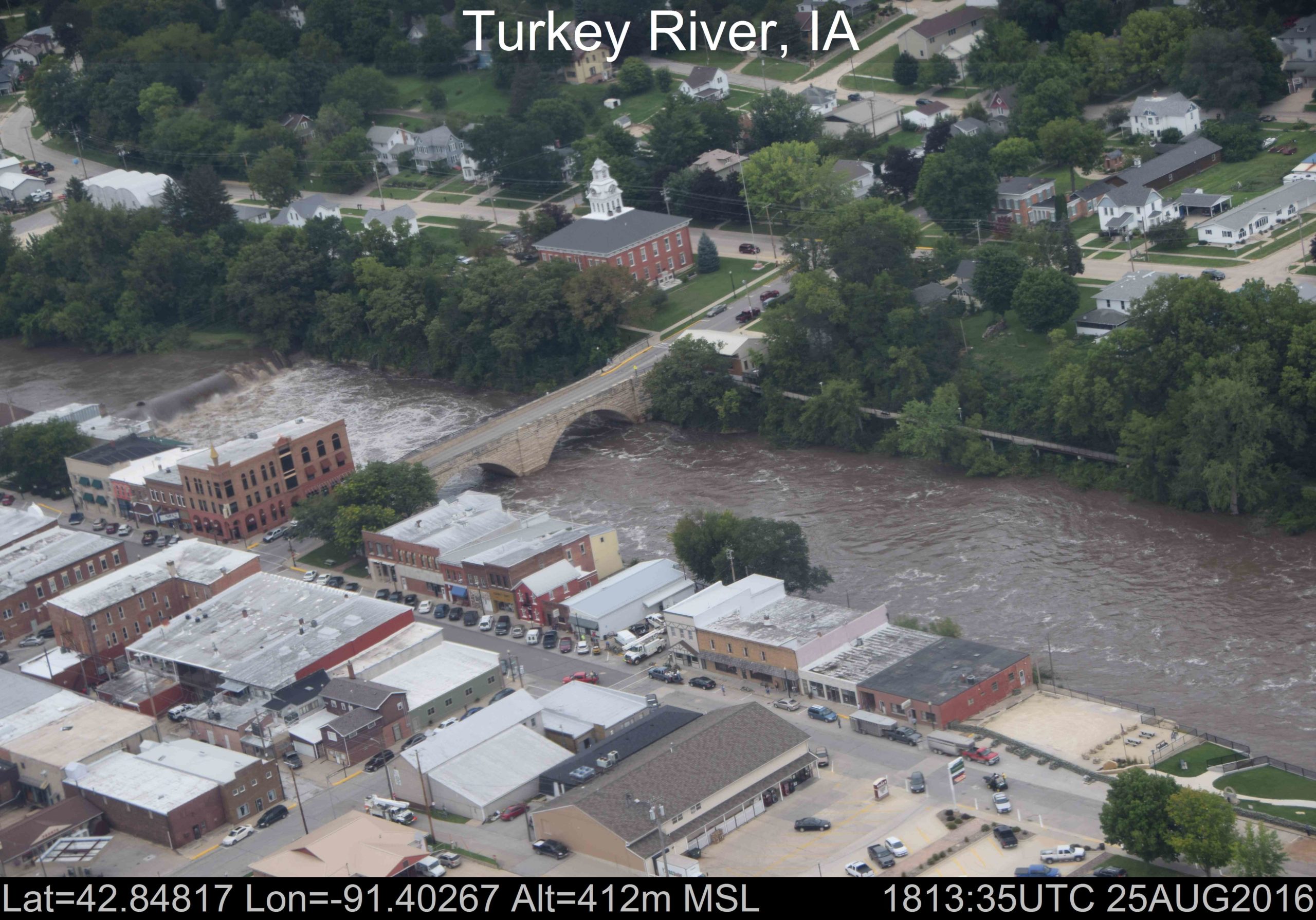

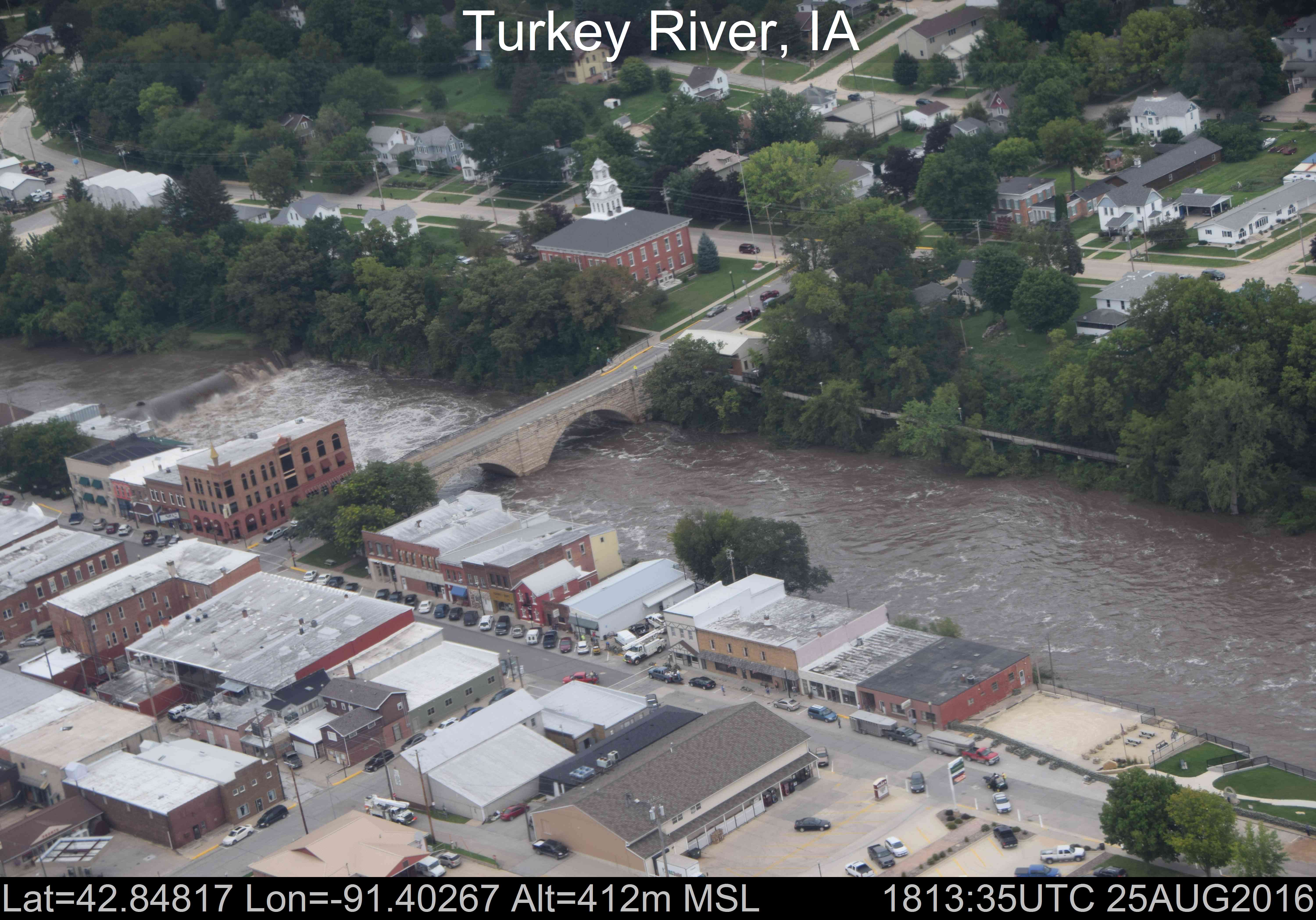

Just a week later, Elkader and other Northeast Iowa residents are dealing with severe flooding from torrential downpours earlier in the week that dumped as much as 8″ of rain in some areas, causing damage to homes, businesses, and even killing one person swept away in the flash floods. Some residents had to evacuate their homes and take shelter elsewhere (including fish!). The water that makes these communities peaceful, beautiful places to live and visit can also pose severe challenges.

Flooding of the Turkey River in downtown Elkader as taken by NOAA’s National Operational Hydrologic Remote Sensing Center’s Airborne Snow Survey airplanes.

This storm is a solemn reminder of the power of water and the importance of studying it. Our seed grant RFP will be released soon, and this year we are partnering with other Water Resources Research Institutes in the Mississippi and Ohio River Basins to share knowledge so that we’re advancing our understanding together. In addition, the Iowa Watershed Approach has already begun work in communities to help address flood and water quality risks and increase community resiliency to events like the ones this week. Related to flooding, up-to-date flood information is available through the Iowa Flood Information System (IFIS).

IWC’s overarching goal is to improve management of water resources. “Management” might not be the best term, because in many cases, water (and nature) does what it will. There’s a parallel between “managing” water and “managing” children – no matter what you want out of it, the true nature of the water (and the child) will always rise up.

One of many attempts at a “nice” family picture at the Keystone Bridge. Getting kids to look at the camera with serene smiles can be as difficult as telling a river or a rain cloud exactly where to run or when to empty.

From the IWC Director: Water Quality – Why Such a Challenge?

On July 26, IWC Director Rick Cruse presented to about 150 attendees at the Arkansas Water Resources Center’s Annual Conference. The theme of the conference was “Nutrients, Water Quality and Harmful Algal Blooms.” Dr. Cruse spoke during the opening general session in a presentation entitled “Water Quality – Why Such a Challenge?” The following is a summary of what he told our downstream friends in Arkansas.

Why is water quality such a challenge? A few simple concepts help recognize why this challenge exists.

We know that water added to a pail filled water will be lost.

We know that complex systems are more difficult to understand and manage than simple ones.

We also know that activities favoring economics of an individual may not favor natural resources or the general population.

And finally, to be a champion one must be willing to identify a goal and be committed to meet that goal.

Transposing these concepts to agriculture is quite simple. Adding nutrients to a landscape that has had repeated nutrient additions and does not have the capacity to hold additional nutrients will likely lose those nutrients as a full pail loses water added to it. Managing nutrients in agricultural systems is incredibly complex; elements of this complex system range from policy influencing human management choices to highly variable weather systems.

Understanding these elements independently is difficult, understanding how they interact is incredibly challenging. Management practices that favor maximum short term economic returns require short term management choices; managing natural resources such as water requires a long term vision. Short term profit motives seldom support long term water quality goals.

Finally, if we want improved water quality, we must make water quality a committed goal and not just an add-on to a system that we know to be very leaky.

Reflections on the 2016 Iowa Water Conference

It’s been a week since the opening of the 2016 Iowa Water Conference, one of the most highly attended events in its ten year history. We’ve been busy tying up loose ends, getting presentations posted on the event page, and even catching a few breaths here and there. A week removed seems like a good time to record some observations about this year’s conference as we look forward to 2017 (yes, already!).

You can’t control the weather. We had the conference three weeks later this year to avoid the inevitable early March “in like a lion” happenings. Mother Nature pretty much laughed in our faces, since the weather at the beginning of March was gorgeous, and the storm Wednesday night prevented several attendees and three speakers from making it to Thursday’s activities. (Absolutely enormous thank you to ISU Brent Pringnitz for setting these speakers up to present remotely in an unbelievably short turnaround period.)

Water is kind of a big deal. We had almost 500 people attend the water conference this year. That’s 100 more than last year. We had more posters, more exhibitors. People care about water so much that they will take two days out of their busy schedules to come learn and talk about it with people they may or may not know. The opening plenary even got media coverage on WHO TV.

The Iowa Water Conference shouldn’t be the only time we collaborate. We’ve received feedback from many people who want to make sure the cross-pollination that the Water Conference fosters stays at the forefront. One way to do that is to plan or attend local conferences/meetings/seminars on more specific interests (like tomorrow’s IGWA meeting in Newton). If you need help planning, let us know – we can help steer you in the right direction. If you’re looking for events, sign up for our newsletter. If you have an event, send it to us and we’ll help promote it.

This is YOUR conference. We made quite a few changes to this year’s conference to reflect the comments left in the evaluations from last year, and from what we can tell, they worked (for the most part). Please continue to send us your ideas throughout the year. We’ll have an open call for presentations during the summer months; you’ll find the announcement on this blog, our newsletter and Facebook and Twitter. We have an amazing core committee of conference planners, but can always use more ideas and voices. If you or your organization might want to be on our list of planning partners, give us a call.

There is a lot more we can say, but we’ll leave it at that for now. What were your takeaways from the 2016 Iowa Water Conference?

Rocks in the River

The following is a piece written by Hank Kohler, originally published in the 2015 edition of Getting into Soil and Water, a publication produced by the Soil and Water Conservation Club at Iowa State University. To request a copy of the 2015 edition, please email millerms@iastate.edu.

It is a short drive to the put-in spot. Arm out the window, I watch fields of corn and beans go by, and though few farms have hay land these days, my nose is alert for the chance to smell a recent cutting. I don’t understand the physics of the sound waves, but I think it’s cool that although I’m going down the road at 60 I can clearly hear the song of a blackbird or meadowlark as I pass by.

The canoe is unloaded just above the stream’s bank. On this trip, like many now, I will be alone. Our children that used to accompany me on these excursions have grown and moved away. It’s a very special day when one can join me now, but this time I’m going solo.

The list of what I take, camping gear, fishing equipment, food, drinks, etc., along with its packing has become routine. I caution myself to never take for granted how special both this place is and how my day will be.

Everything left in the canoe I drive downstream to the take-out. I’ve never had anyone bother my stuff while I was gone. Dad told me years ago that if you can’t trust a fisherman, who can you trust, and I guess I’ve been fortunate so far to have had only anglers notice my unattended supplies.

With the truck left at the county park, I mention to the camp host that I will be on the river for the night. I don’t want anyone to wonder if some guy had trouble upstream.

And so it begins. Since I am now where I will get out tomorrow, I need to pedal my middle-aged mountain bike out of the park, up the hill and back to the canoe. The total trip is only about five miles, with the last mile and a half being smooth black top. The start and longest stretch is gravel, hopefully packed hard, not loose with small drifts of sand.

The incline out of the stream’s valley is a bear. Geared way down I pass trees and fence posts slowly and then even more slowly. This is my first trip of the year. Did the winter and passing months take too much of a toll? The front wheel wobbles, I hit a stone or two that I should have missed, but I make it. That’s good, I think. Satisfied with my effort, I sing a bar or two of Three Dog’s Night “Out in the Country”, and head for the canoe.

Once on the river, the first one I meet will be Andy’s. Kerry’s is the largest and just past Robyn’s is the best place to camp. I will paddle by hundreds of rocks today but only three will be oh so special.

The “That rock’s mine” tradition started when our son was first old enough for a river trip. Asking many questions as kids do he wanted to know who owned the rocks we passed by. I replied that they were part of nature, no one had title to them and you couldn’t move the big ones if you wanted to. “I’ll tell you what,” I continued, “why don’t you choose one, call it yours, and you can see it every time we come back.” Not being particularly patient or picky, he immediately pointed to a boulder in the middle of the river right in front of the canoe. It has been his rock and our river barometer to gauge its water level ever since.

That was almost 30 years ago now. Our daughters’ rocks were chosen when it came time for their first float, and they both were more selective. Decisions that seemed final were changed at the next bend. Short-term favorites were replaced as if later in life they were trying on shoes or buying a purse. Imagine that.

Passing Andy’s rock, I notice it is half submerged and smile. “Perfect” comes to mind. The ease of the float and chance for good fishing should be just right.

Every time I dip a paddle in the current or slowly drop an anchor above a snag that may provide supper, I marvel at the river’s beauty. I am sure that a 200 yard hike in either direction would put me in cropland but I see no fields from my canoe. Instead, I am treated to high green canyons formed by maples, walnuts, cottonwoods and willows. They capture and hold the aroma of stink bait, the whistle of wood ducks and the scolding chatter of kingfishers.

Anchoring across from Kerry’s rock I think of the times spent here with my kids. Looking down the river valley is like staring into a kaleidoscope of brightly colored memories. I view friends, family and fish from years past. My children appear of all ages from the first time on the river to the present. I can see their smiles, hear their laughter. Images appear to float on the breeze and current like the cottonwood fluff. Here for a second, then drifting away only to be replaced by another. They cover the canoe, the river, and my thoughts with warmth.

A tug on the line jolts me back to the present. The fight is on. It hasn’t surfaced like a channel cat or jumped like a small mouth. It’s hooked on my night crawler pole so it could be one of a dozen species that the stream holds. Not having seen it yet I enjoy the resistance created by the strength of the fish and current of the river. Hopes of walleye fillets sizzling in the skillet start to rise, but soon I am gently releasing a brilliant scarlet and silver red horse. Once you get past the lips it is by far the most beautiful fish in the river. Having kept a few catfish I watch the up and down flight of a red-headed woodpecker as I paddle towards Robyn’s rock and a sandbar camp.

Passing by banks filled with nesting swallows my mind drifts with the current, and I, too, start to wonder about the rocks. Where did they come from? How old are they? Compared to their age my entire life is just a wing beat. I try not to, but sometimes I feel my years. I used to sing “Sunshine on my Shoulders” while I paddled shirtless, grateful for the strength I had in the two of mine. Now they throb at times. As I’ve aged my body has become a ledger of additions and subtractions. A new hip and an ankle brace show up on the plus side, while strength, flexibility and the hair that used to adorn my top-knot have all become minuses.

I know that day will come when I won’t float the river. That day will come when I can’t bike the hill, lift the canoe, raise anchor or paddle the rapids. Yes, that day will come.

But it will not be today! Not today!

Catfish cleaned, I take a strong stroke. Shoulders hardly ache. Another stroke and they are almost healed. As I approach Robyn’s rock I seem to gain strength with every bend of the river.

Perhaps these are the life sustaining waters Ponce DeLeon sought so many years ago. Perhaps for me they are even more special. Completely immersed with appreciation for what the river has given and still provides, I start to sing ELO’s “Mr. Blue Sky” when I see them. Up ahead in the shallows, three children laughing, splashing, skipping stones. Their magical aberration calls to me “Put in here Dad, we’ve been waiting. Camp’s set up.”

Paddle at rest, it’s the current alone that guides me to shore.

Through the portal of time.

Past the rocks in the river.