Getting into Soil and Water 2020

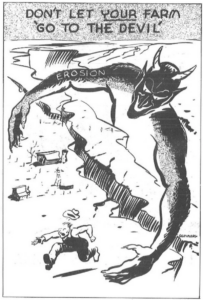

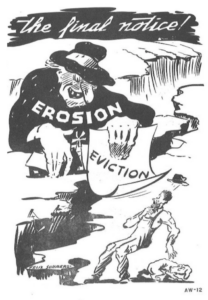

Artists are not usually the first people who spring to mind when thinking about soil conservation in the United States. In the 1950s and 60s however, Felix Summers’ artwork introduced the Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resources Conservation Service) and big ideas about conservation farming to thousands of Americans. Even if they did not know his name, rural communities knew Felix Summers’ vivid, one-panel cartoons pointing out the dangers of soil erosion and the value of conservation farming.

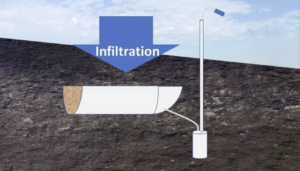

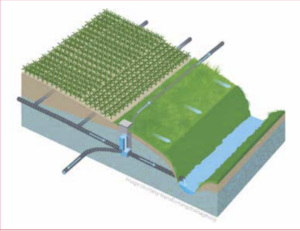

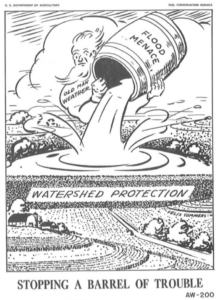

In the mid-20th century, the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) used a team of technical illustrators in the Information Office to bring SCS ideas and publications to life. Professional artists illustrated complex scientific and engineering concepts not easily conveyed in text or photography. The tremendous number of informational bulletins, pamphlets, and other materials that flowed from the SCS in the mid-20th century often featured the work of these in-house illustrators. While most of their work illustrated specific manuals, guides, and public-facing pamphlets, the Information Division also provided a constantly expanding catalog of conservation cartoons to field offices. Field office staff across the country published the cartoons that best addressed local issues in local newspapers. These cartoons were many Americans’ first introduction to the SCS and conservation agriculture. Most of the over 400 cartoons in the artwork catalog were the work of one illustrator, Felix Summers.

Making His Way to the SCS

Felix Summers came to the SCS by way of two very different places: the New York City art scene of the 1930s and the Mills County Iowa SCS office. He began his art career at the University of Nebraska and went on to do post-graduate work at Yale, where he studied with muralist Eugene Savage. Summers’ style reflected the contemporary influence of the Regionalist school made famous by other Midwestern artists such as Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood. Iowan farmers since before the Civil War, Summers’ family was steeped in agriculture. His rural upbringing outside of Strahan, Iowa informed his artistic focus on scenes of agrarian and rural life. Despite his rural roots, Summers spent five years painting murals in decidedly non- rural Manhattan department stores and nightclubs, including the storied Cotton Club and the El Morocco. World War II deferred Summers’ early artistic career as a muralist when the Army drafted him to serve with the combat engineers. After the war, the art world’s tastes moved away from Summers’ agrarian Regionalism – rejecting the familiar, rural scenes that were his specialty.

Showcasing His Skills

Looking for work after the war, Summers returned home to Iowa and took an entry-level job as a conservation aid at the Mills County office of the SCS. His skill at the drafting table lent itself well to conservation planning. Combining a growing belief in the mission of the SCS with his desire for artistic expression, Summers spent his evenings and weekends drawing cartoons designed to spread the gospel of soil conservation. His work drew the attention of SCS leadership, and he was soon promoted to the regional office in Milwaukee as a full-time illustrator. Beginning in 1948, the SCS began distributing Summers’ cartoons nationally. An agency reorganization moved Summers to Lincoln, Nebraska where he worked as an illustrator in the Midwest Regional Technical Service Center until his retirement in 1972. Upon his retirement, Summers received the USDA’s Superior Service Award for his illustrative work in service of conservation. Felix Summers died in 1987 at the age of 77.

Reaching a Wider Audience

The work of illustrators like Summers helped the SCS reach a wide audience not already familiar with the work of the SCS or the conservation movement. Cartoons provided a shorthand that quickly and succinctly conveyed why the work of the SCS mattered. Photographs provided examples, but art conveyed big ideas quickly and succinctly. Armed with something to say about conservation, the same artist who was out of style in post-war Manhattan nightclubs was right at home in midwestern newspapers. Summers’ cartoons drew in people who would ordinarily scan past what might have seemed like dry and technical articles about federal conservation efforts. Moreover, he conveyed SCS messages in a visual shorthand that spread the word to even the casual reader. When interviewed in 1952, Summers summed up his artistic approach: “to speak the language of farmers on their own terms, but do it pictorially. I wanted to interpret for other people all the sweat, strain, and worry that goes into farming.”

By summing up the importance of conservation agriculture in one panel cartoons, Summers provided an extremely efficient message that reassured those farmers and ranchers already practicing conservation and challenged those who were not. A New York muralist might seem an unlikely champion for conservation, but Summers widely distributed work remains a testament to the importance of a truly interdisciplinary approach to conservation.

Shelby Callaway

Historian, Natural Resource Conservation Service US Department of Agriculture