Post submitted by Emily Martin, MS Environmental Science student at Iowa State University and recipient of the Graduate Student Supplemental Research Competition

Since the last update, we switched the focus of our study to the ability of biochar to remove nitrate in comparison to a woodchip-only bioreactor. As a reminder, the original goal of the project was to evaluate the ability of woodchip bioreactors to remove phosphorous by adding biochar as a phosphate (P) amendment. In the previous update, we found in a P sorption study that none of the biochars performed well at removing P from solution.

To compare nitrate removal, we ran what is called a batch reactor test. The batch test used five liter buckets filled with 30 grams of biochar, 350 grams of Ash woodchips, and three liters of deionized water. As a control to see the real impact of adding biochar, some buckets only contained woodchips. Both the test and control buckets had three types of denitrifying microbes added: Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Pseudomonas stutzeri, and DN-8A.

One issue that can arise not only in batch tests, but also in field woodchip bioreactors is an initial flushing of nutrients from the woodchips, and as we found out in the P sorption tests, also from biochar. To prevent this affecting our batch reactor tests, we allowed the mixture to soak for 24 hours. After the initial soak, the buckets were drained of the deionized water and two liters of nutrient solution was added. The nutrient solution was made to 30 mg/L NO3– and 10 mg/L PO42- using KNO3 and KH2PO4 – PO4 with deionized water, respectively. Samples were taken at 0, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours to test for NO3—N.

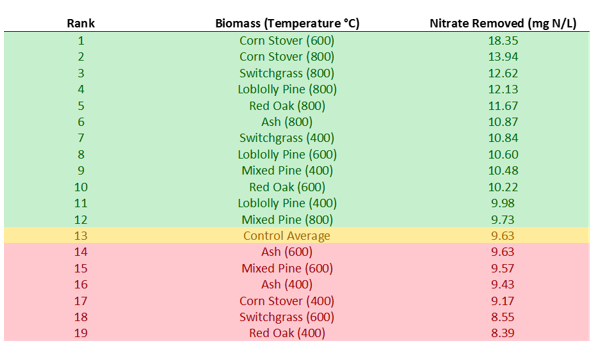

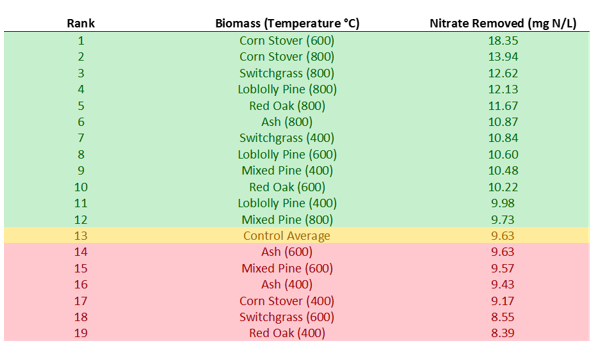

Results showed that 12 of the 18 biochars removed more nitrate than the woodchip control. The biochar with the most removal was the 600°C Corn Stover, which almost doubled the amount of nitrate removed by the control. Of the 12 biochars that removed more nitrate than the control, 50 percent were 800°C, 25 percent were 600°C, and 25 percent were 400°C. All six of the 800°C biochars performed better than the control. The nitrate results overall were more promising than what was found in the P sorption test. There is potential to increase the ability of field bioreactors to remove nitrate by adding biochar; however, more tests will be needed to see how the biochar handles scaling up and field conditions. This was a short-term test in a laboratory setting. It is possible that on a larger scale, longer timescale, and at varying influent nitrate concentrations, biochar could perform worse than seen in the lab.

A secondary part of the batch test was following up to the P sorption test. Because the biochar leached phosphorus in the P sorption test, the 24 hour soak in deionized water should have helped remove the initial leaching. We are still testing all of the biochars, but initial results from a set of three biochars and the woodchip control showed that all still leached phosphorus into the solution. This could be problematic for the use of biochar in field conditions and should be managed if tests are taken to full-scale.

The next step for the project is to finish testing for phosphorus removal from the batch tests. After that, a paper will be written and submitted for publishing. As conferences are coming up this spring, I will be creating a poster to present at the Iowa Water Conference (March 21-22) and the Environmental Science Graduate Student Symposium (April 4).