Written by Sarah Feehan

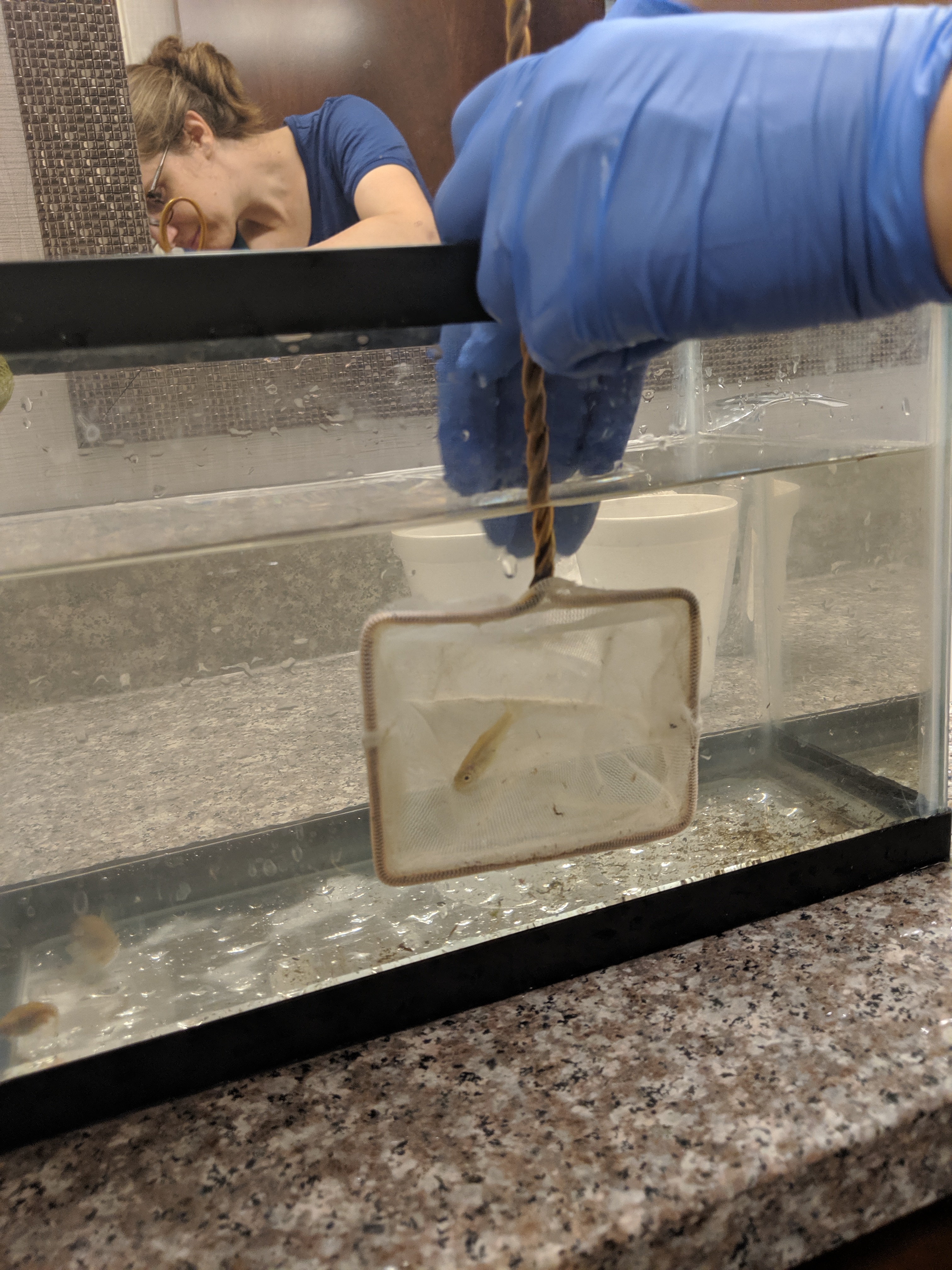

Lab-reared, native minnows have been living in fish cages placed in a stream for the last four days, and now a team of researchers collects them to study the impacts of water quality on aquatic organisms.

For nearly the past two years, these researchers have been measuring chemical concentrations in the same stream, and this caged fish experiment is one of the ways researchers are connecting chemical presence in the environment to possible biological effects.

Greg LeFevre, an assistant professor of environmental engineering and faculty research engineer for IIHR at the University of Iowa, studies water quality, wastewater, and toxic substances.

LeFevre, a principal investigator (PI) of the study, is researching what happens when pharmaceuticals enter our waterways. His research is funded through a National Competitive Grant under the USGS 104(g) Program. A goal of this program is to promote collaboration between the USGS and university scientists in research on significant national and regional water resources issues.

This working group consisted of representatives from the University of Iowa, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, and the United States Geological Survey (USGS). There were PIs, graduate students, and USGS scientists.

“We have a number of different things we are working on both in the lab and in the field to try and answer the questions comprehensively through multiple fields of expertise,” LeFevre says. “And out of this one grant, because there are so many things coming out of this, we hope that this field site will be the locus for a bunch of other research.”

Wastewater-derived contaminants of emerging concerns (CEC) have demonstrated harmful effects to aquatic organisms. LeFevre believes that there is a critical need to understand how the changing complex mixture composition of CECs relates to biological effects. This understanding is critical in order to better protect ecosystem health in freshwater resources and inform stakeholder decisions.

“Everything that happens on the land is ultimately very connected to what goes on and into the water,” says LeFevre. “What we want to do is to develop some kind of understanding of the exposure to fish as well as some of the biological facts that are going on there.”

They hope to see the effects on fish throughout different areas of the stream. They will study a control group that permanently remains at the lab, a different group released in cages in the waterway after being brought up in the lab, and native fish who have spent their whole lives in the natural stream.

The waterway they are putting fish in and pulling fish from comes from an upstream wastewater treatment facility LeFevre describes as, “one of the best in the state.”

The North Liberty Wastewater Treatment Plant, upstream of the tested waterway, has a membrane bioreactor, zero E. coli that comes out of the plant, and biological phosphorus and nitrogen removal. All of which is far beyond the permit requirements.

Rebecca Klaper, professor at the School of Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, is a co-principal investigator on the study has also been a key collaborator to LeFevre’s research.

Regarding the data, Klaper explains, “The detection part is fantastic and the fact that we’ve gotten so much better at measuring these things is great. We might detect hundreds of chemicals in the water, but they might have no effect at all. So, the other part is trying to figure out if we really need to be concerned about them.”

“Today has been really exciting,” PhD candidate and research assistant at the University of Iowa Hui Zhi says. Zhi is one of four Iowa Water Center (IWC) Graduate Student Research Competition recipients for 2019.

“I think we were overprepared, which is great,” she says. “Having everything ready to go makes our work more efficient. And we also have so many people from our labs working together, making everything work very smoothly.”

Part of Zhi’s research through the IWC grant encompasses the sorption and biodegradation of pharmaceuticals in Iowa’s water. “It’s important we understand what’s in our drinking water, what’s in the treated wastewater, and what’s in the streams and rivers,” Zhi says.

Sarah Feehan is the communications specialist for the Iowa Water Center. She holds a BS in Journalism and Mass Communication with a minor in Political Science from Iowa State University. In fall of 2019, Feehan will begin acquiring her JD from Drake Law School.