Rick Cruse, Professor in the Agronomy Department at Iowa State University and Director of the Iowa Water Center, has a deep appreciation for a resilient outdoor world that energizes his soils research and graduate teaching activities.

Continue reading2018 Practical Farmers of Iowa Annual Conference

Post submitted by Tianna Griffin, the Iowa Water Center’s Special Projects Assistant

Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI) 2018 Annual Conference was an event that brought families, farmers and professionals together to learn and meet new people. It was my first time attending a conference and it won’t be my last.

The event was from January 18-20th and there were approximately 1,000 people who attended. This conference opens the opportunity for students, farmers, professors, and professionals in natural sciences to come together to learn new things and network. The conference theme was “Revival.” As the conference program stated, “At Practical Farmers, we believe that revival – of rural communities; of our soil, creeks and rivers; of opportunities for young people to set down roots where they grew up – is vital for agriculture, people and the land.” The topics presented, and the overall dynamics of the event exceeded my expectations. I didn’t know what to expect attending a conference; there were more people there than I expected, it was a family oriented event, and the set-up was conducive to interacting with others.

The event was filled with friendly and professional people. I saw many familiar and new faces. There was a wide variety of exhibitors to network with who specialized in animal feed, tillage practices, organic production, and many more. A silent auction was held, and sessions to attend ranging from, “Teaching Livestock to Eat Weeds,” “Pragmatic Approaches to Sustainability and Profitability,” “Leaving Your Legacy,” and many more. There were two sessions on Friday, and five sessions on Saturday that were 70 minutes long. The presenters were a diverse set of people who were farmers that grow row crops as well as horticultural crops. There were ISU professors, as well as professionals who had expertise in certain areas of agriculture. This was the most impressive aspect of the conference because it allowed for a variety of available sessions. It allowed me to step out of my comfort zone of attending more than just topics on horticulture crops (which is my academic minor) and attend sessions that I otherwise wouldn’t have had the opportunity to attend.

Some sessions that I attended and enjoyed were “Ecology and Management of Iowa’s Common Vegetable Insect Pests” presented by Dr. Donald Lewis who is an ISU entomologist, “Learning from On-Farm Research: Horticulture,” presented by Carmen Black, Rob Faux, and Liz Kolbe. Black and Faux are growers who practice on-farm research. Lastly, “Using Tea Bags to Assess Soil: A Low-Cost Approach?” presented by Marshall McDaniel who is an assistant professor at ISU in agronomy. I learned many new things by attending the conference as well as got a refresher on things of which I already had knowledge. There were so many good topics being presented that I didn’t know what to choose.

I enjoyed going to the PFI Annual Conference. It was a successful event because they represent people with different backgrounds of expertise; professionals and families attended the event. Because there’s a variety of different speakers it allows for the opportunity to learn new things and meet new people. Events like the PFI Annual Conference makes the possibility of their conference theme “Revival” come true by bringing farmers and town people together. According to PFI’s conference website, by “Revival,” PFI envisions repopulating rural areas with farmers, regenerating Iowa soils by diversifying crop rotations, rejuvenating creeks and rivers, and opening opportunities for the next generation of farmers.

Tianna Griffin is Iowa Water Center’s Special Projects Assistant. She is pursuing an undergraduate degree in agronomy with emphasis in agroecology and minoring in horticulture with an emphasis in fruit and vegetable production.

Tianna Griffin is Iowa Water Center’s Special Projects Assistant. She is pursuing an undergraduate degree in agronomy with emphasis in agroecology and minoring in horticulture with an emphasis in fruit and vegetable production.

Get to know your soil

Photos of the 2017-2018 Agronomy in the Field cohort for Central Iowa at the ISU Field Extension Education Lab. Photos by Hanna Bates.

An education in soil sampling

Last week I attended Agronomy in the Field, led by Angie Reick-Hinz, an ISU field agronomist. The workshop focused on soil sampling out in a field. The cohort learned a lot of valuable insight into not only the science of soil sampling, but also practical knowledge from out-in-the-field experiences.

Taking soil samples in a field is critical in making decisions about fertilizer, manure, and limestone application rates. Both over and under application can reduce profits, so the best decision a farmer can make is based on a representative sample that accurately shows differences across his/her fields.

What do you need?

- Sample bags

- Field map

- Soil probe

- Bucket

When do you sample?

After harvest or before spring/fall fertilization times. Sampling should not occur immediately after lime, fertilizer, or manure application or when soil is excessively wet.

Where do you sample?

Samples taken from a field should represent a soil area that is under the same type of field cultivation and nutrient management. According to ISU Extension, the “choice of sample areas is determined by the soils present, past management and productivity, and goals desired for field management practices.”* See ISU Extension resources for maps and examples for where in the field to take samples.

Most importantly…

Like with everything that happens out in the field, it is important to keep records on soil testing so that you can evaluate change over time and the efficiency of fertilizer programs. As we say at the Iowa Water Center, the more data, the better! The more we learn about the soils, the better we can protect and enhance them. Healthy soils stay in place in a field and promote better crop growth by keeping nutrients where they belong during rain events. Not only can we monitor soil from the ground with farmers, but with The Daily Erosion Project. These combined resources, with others, can provide the best guidance in growing the best crop and protecting natural resources.

Interested in Agronomy in the Field? Contact Angie Rieck-Hinz at amrieck@iastate.edu or 515-231-2830 to be placed on a contact list.

* Sawyer, John, Mallarino, Antonio, and Randy Killorn. 2004. Take a Good Soil Sample to Help Make Good Decisions. Iowa State University Extension PM 287. Link: https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/files/article/PM287.pdf

Hanna Bates is the Program Assistant at the Iowa Water Center. She has a MS in Sociology and Sustainable Agriculture from Iowa State University. She is also an alumna of the University of Iowa for her undergraduate degree.

Identifying Indicators for Soil Health

Breaking down our knowledge of soil enzymes

Post written by Marshall McDaniel, Assistant Professor in the Department of Agronomy at Iowa State University

As mentioned in a recent Washington Post article, there is a zoo beneath our feet in the soil. There are three properties of the soil, which are physical, chemical, and the biological properties. The emphasis on soil biology is, in large part, what separates soil health from the concepts of soil quality and the physical properties of soil (also known as soil tilth). After all, only something that is living can be healthy (or unhealthy). Many soil organisms are like us humans in that they require carbon as their main source of food in order to grow and reproduce. Extracellular enzymes are proteins produced by microorganisms in soil to acquire carbon and nutrients from soil organic matter.

The McDaniel Lab was one of five to receive the Soil Health Literature and Information Review Grants from the Soil Health Institute. We will do a quantitative literature review on two of these enzymes – beta-glucosidase and polyphenol oxidase. Beta-glucosidase can generally be thought of as being used for easily broken down, or labile, forms of soil carbon, and polyphenol oxidase for recalcitrant carbon. In other words, think of labile carbon as a buffet of ‘yummy and healthy’ food that is nutritious and easy-to-digest for soil microbes, while recalcitrant carbon can be thought of as the equivalent of broccoli stems to human digestion. We want to manage soils so that there is a large amount of the ‘yummy and healthy’ soil carbon for microbes to eat, and less of the ‘broccoli stems’.

Where the enzymes come in is that soil microbes will produce more of the beta-glucosidase enzyme if there is more ‘yummy and healthy’ forms of carbon in the soil, because it helps them to metabolize this form of carbon. Conversely, if all you have left in the soil are ‘broccoli stems’, then as a soil microbe you are going to produce more polyphenol oxidase to metabolize this difficult to break down source of food. Therefore, the ratio of these two enzymes holds promise as a good biological soil health indicator since it is an index of supply-and-demand for ‘yummy and healthy’ microbe food over ‘broccoli stems’.

What does this have to do with water?

Soil health and water quality go hand in hand. Improved soil health has the potential to increase water infiltration, increase water holding capacity, decrease surface runoff, decrease soil erosion, increase nutrient retention in the soil for plants, and more. By improving understanding of our soil biology, we can both better serve our natural resources and crop production.

Soil – Agriculture’s Reservoir

Post submitted by Hanna Bates, Program Assistant for the Iowa Water Center

The soil is like a sponge that holds water so it is available when crops need it. Wetter soil at the surface prevents deeper infiltration and so water is lost as surface runoff. Not only this, but soil moisture is also a variable that influences the timing and amount of precipitation in a given area. This is due to the impact it has on the water cycle. This cycle circulates moisture from the ground through evaporation and plant transpiration to the atmosphere and back to the ground again through precipitation. Therefore, the amount of water stored in the soil can affect the amount of precipitation received during the growing season.

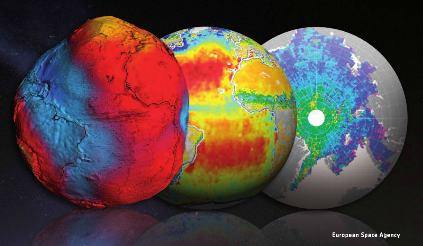

According to Hornbuckle (2014), “we enter each growing season ‘blind’ as to whether or not there will be enough soil moisture and precipitation to support productive crops.” If there were a way to document and record water storage in the soil besides field measurements, we would have a better ability to predict future weather patterns and therefore, make better field decisions. Satellite remote sensing tools such as the European Space Agency’s Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) and NASA’s Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) can be used to take such measurements. Before these tools can be used to estimate water storage and improve weather and climate predictions, researchers must compare them to what is actually measured within the soil. This process of confirming accuracy of a tool is called validation.

A project led by Dr. Brian Hornbuckle, and funded by the Iowa Water Center in 2014, sought to improve and validate SMOS and SMAP in near-surface soil moisture observations of Iowa. Hornbuckle used a network of soil moisture measurements located in the South Fork Watershed as a standard to validate the accuracy of SMOS and SMAP. At each site, soil moisture and precipitation was measured.

Some of the results of this research project are presented in a 2015 article published in the Journal of Hydrometeorology. Rondinelli et al. found that SMOS and the network of soil moisture measurements detect different layers of the soil. SMOS takes measurements of the soil surface while the network observes a deeper level of soil. These results will allow scientists to better evaluate the accuracy of measurements from SMOS and SMAP and ultimately enhance our understanding of the water content of the soil surface. As noted earlier, it is this layer of the soil that determines how much precipitation is lost to surface runoff.

In a subsequent study published in 2016, Hornbuckle et al. published further results that indicate new ways of using SMOS. Researchers found that SMOS can be used to look at water in vegetation, as opposed to water in the soil. Hence SMOS might be used in the future to observe the growth and development of crops, and perhaps estimate yield and the time of harvest as opposed to conducting field surveys from the ground. It also has the potential to measure estimates of the biomass produced during the growing season, which could be useful to reach bioenergy production goals.

Research like this demonstrates that a single tool can be used in multiple ways to better understand our landscape. Not only this, but preliminary studies of SMOS also show that it is important to verify the accuracy of tools before relying on them. Like all research, the work is not done to identify all the potential uses for SMOS and SMAP. A new NASA grant, in partnership with the Iowa Flood Center, will help get researchers even closer to making satellite measurements a useful, scientific tool to understand water near the soil surface.

References

Hornbuckle, Brian K. “New Satellites for Soil Moisture: Good for Iowans!.” A Letter from the Soil & Water Conservation Club President (2014): 20.

Hornbuckle, Brian K. Jason C. Patton, Andy VanLoocke, Andrew E. Suyker, Matthew C. Roby, Victoria A. Walker, Eswar R Iyer, Daryl E. Herzmann, and Erik A. Endacott. 2016. SMOS optical thickness changes in response to the growth and development of crops, crop management, and weather. Remote Sensing Environment (180) 320-333.

Rondinelli, Wesley J., Brian K. Hornbuckle, Jason C. Patton, Michael H. Cosh, Victoria A. Walker, Benjamin D. Carr, Sally D. Logsdon. 2015. Different Rates of Soil Drying after Rainfall Are Observed by the SMOS Satellite and the South Fork in situ Soil Moisture Network. Journal of Hydrometeorology. April 2015.

Planning for Watershed Success in Eastern Iowa

Post edited by Hanna Bates, Program Assistant at the Iowa Water Center

This week, we chatted with Jennifer Fencl, the Solid Waste & Environmental Services Director at The East Central Iowa Council of Governments (ECICOG). Fencl works to bring eastern Iowa stakeholders together to better manage their natural resources and to create a long-term investment in their community. Below are a few highlights from our conversation that outlines some of the behind-the-scenes work in watershed planning.

Please describe your work in watershed management in Iowa.

The East Central Iowa Council of Governments (ECICOG) became involved in watershed management in 2011 when the City of Marion requested assistance in applying for Watershed Management Authority Formation grant funding from the Iowa Economic Development Authority (IEDA) for the Indian Creek watershed. The Indian Creek Watershed Management Authority (ICWMA) was formed under Iowa Code 28E and 466B in August 2012 with 6 of the 7 eligible jurisdictions agreeing to plan for improvements on a watershed level. Funds were made available in 2013 by the IEDA to complete watershed management plans to address flood risk mitigation and water quality. The ICWMA received one of the three planning grants and engaged in a multi-jurisdictional planning approach facilitated by ECICOG in partnership with several local, state, and federal agencies. The resulting Indian Creek Watershed Management Plan (ICWM Plan) identifies strategies and recommendations for stormwater management and water quality protection, including specific implementation activities and milestones. The ICWM Plan was completed and presented to the public in June 2015 and adopted by all six of the ICWMA members at policy maker meetings during July and August of 2015.

As the ICWMA Plan was wrapping up, the City of Coralville requested ECICOG’s assistance in forming a WMA for the Clear Creek watershed. In this case, Coralville was willing to sponsor the WMA formation and planning grant application services. The Clear Creek Watershed Coalition (CCWC) formed as a WMA under Iowa Code 28E and 466B in October 2015 with all 9 of the eligible jurisdictions joining. ECICOG secured DNR watershed planning funds early in 2016 and the CCWC is mid-way through their planning process. Fortunately, the Clear Creek watershed was one of the eight watersheds selected for the Iowa Watershed Approach HUD grant project. The additional watershed planning funds from the HUD grant will add significantly to the resulting watershed plan.

In early 2016, the Middle Cedar Watershed Management Authority (MCWMA) was on its way to formally becoming a WMA and needed some help in completing the agreement filing, developing by-laws, and organizing the Board of Directors. ECICOG assisted the MCWMA in forming under Iowa Code 28E and 466B in June 2016 with 25 of the 65 eligible jurisdictions joining. The MCWMA is one of the eight watersheds selected for the Iowa Watershed Approach HUD grant project.

What are the challenges and rewards in doing work with watershed management?

One challenge that became clear in the Indian Creek process was the disconnect between the watershed (technical) assessment and the local stakeholders. That gap must be bridged to develop meaningful, locally-based goals and implementation strategies. For me, the reward is watching the interaction between perceived “enemies” (urban/rural; big city/suburb; ag producer/government type) and bringing skeptical people into the process to develop an actual plan… that they ultimately agree to.

What kinds of stakeholders are involved in developing a watershed management plan?

It is critical to include the local Soil and Water Conservation District, government representatives, and the landowners (both urban & rural, flood impacted if possible) in developing goals and strategies. I believe that it is also important to identify the ‘experts’ in your watershed, both locally and from state agencies, early on and have them provide input on what assessment activities and planning services are really needed from an outside consultant. There is a role for everyone to play.

What are the basic steps in putting together a watershed management plan?

Here is my road map:

- Invite participation

- Identify resource concerns

- Assemble experts

- Complete assessment work

- Present the assessment to a broad list of stakeholders (need good interpreters)

- Develop goals, define implementation strategies, and prioritize the strategies

- Compile the plan and present the plan for comment

- Shop the plan for formal adoption by policy making board/councils.

What is one piece of advice you’d give to those wanting to develop a watershed plan for their community?

Run… kidding, sorta. Seek help from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources and Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship basin coordinators first, and then gauge the interest of the other entities in the watershed. You need to find some champions to help smooth the way for local elected officials.

Daily Erosion Project goes International

This week Dr. Richard Cruse, Professor in Agronomy at Iowa State University and Director of the Iowa Water Center, was invited to speak at the Rendez-vous végétal 2017 in Quebec, Canada. He provided a presentation on the cost of soil erosion and introduced the Daily Erosion Project to an international audience of soil and water professionals.

Continue readingIntroducing the Iowa Watershed Approach

The Iowa Watershed Approach (IWA) is a new five-year project focused on addressing factors associated with flood disasters in the state of Iowa. The IWA project will also provide benefits of improved water quality by implementing conservation practices outlined in the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy.

Continue readingGeographic Information Systems at Iowa State University

Big data requires big software and big ideas. This can be especially true when it comes to managing our water-related resources. Today, we have access to numerous data points about our soil and water that can assist in understanding current landscape conditions and to plan for the future. Information such as this is not useful unless it can be analyzed by the experts using software such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

Continue readingGet to know the Rathbun Land and Water Alliance

The Rathbun Land and Water Alliance was established in 1997 to promote cooperation between public and private sectors in an effort to protect land and water resources in the Rathbun Lake Watershed. The Rathbun Lake Watershed is located in the six southern Iowa Counties of Appanoose, Clarke, Decatur, Lucas, Monroe, and Wayne and covers 354,000 acres. Rathbun Lake is the primary water source for Rathbun Regional Water Association, which provides drinking water to 80,000 people in southern Iowa and northern Missouri.

Continue reading