Water Scholars Book Club 2021 June Book. Follow along as we post book reviews, resource lists, and content each month to support learning about a particular water topic.

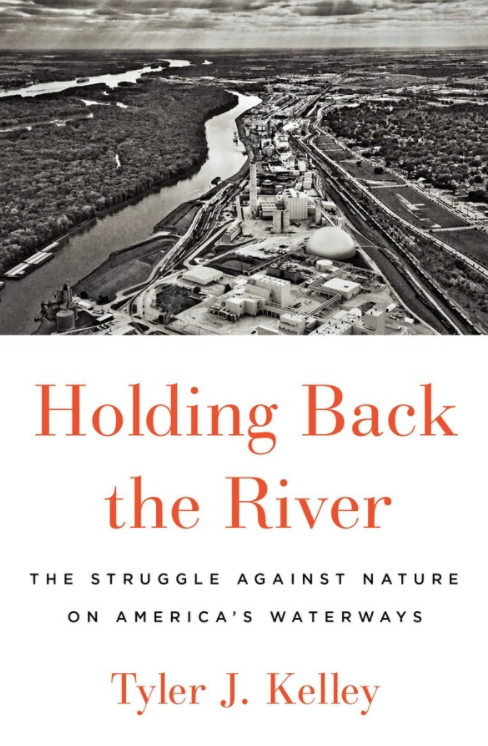

In Tyler J. Kelley’s book, “Holding Back the River: The struggle against nature on America’s Waterways,” the author explores the history of the US attempting to tame its rivers through engineering and infrastructure policies, as well as gives an in-depth look at the people working to hold the water within the streambanks.

By Hanna Bates, Assistant Director, Iowa Water Center

Quick Summary of the Book: The investigative reporting of the author provides an in-depth look at the history of water infrastructure in the Midwest and the policies that sought to conquer and control our waterways. But as we face climate change, we may need to think beyond rebuilding old systems and considering a new mindset as we consider the power of our waterways.

Why we selected it: There has been increasing focus on the aging infrastructure that supports transport and commerce in the US with the introduction of the American Jobs Plan. This book explores the aging infrastructure that makes the water systems in the US navigable for commerce, particularly agriculture commodities. This book heavily focuses on the complexity of work the Army Corps of Engineers has to secure streambanks with levee systems along Midwestern waterways to minimize risk and damages. In 2019, Iowa was subject to breached levees that led to billions of dollars in damages due to flood waters in Southwestern Iowa.

_

When I was a kid growing up in Southwest Iowa, I lived on a farm about a mile from town. A major divider between us and access to groceries, the post office, and school was the Nishnabotna River. One summer the river crested so high it spread into nearby low-lying fields, a nearby business or two, and eventually spread over the highway, our only access to town. What was normally a 10-minute drive would become an over 40-minute to drive in the opposite direction to find a dry road on a roundabout drive to access town. These memories came flooding back as I read through Kelley’s investigative reporting on policy attempts to tame the water that often fails nature or vulnerable populations along the water.

“You don’t own the land; the land owns you” – Faulkner

Kelley explores river management of the Mississippi, the Missouri, and the Ohio rivers predominantly through the history of the Army Corps of Engineers and their purpose to maintain infrastructure on US waterways to support the navigation of commodities along with providing risk reduction for flooding disasters along waterways and coastal lines.

The author also explores belief systems regarding flooding and flood management that dictate decision-making for those along the river, often showing that our perspectives of water has not kept pace with the ever-growing threat of climate change and increasing rain events throughout the Midwest. The typical approach in the past is that when fields and homes flood, we rebuild again. Significant floods are considered rare, and so once an event happens some may assume that it will never happen again. The prelude opens with the story of a farmer in Southwest Iowa. Following a previous flood event in 2011, the farmer cancelled his flood insurance in 2018 and assumed that the protection measures in the area had been robust to protect his land. He states in the book that he would not anticipate a flooding event like in 2011 until after he was dead. Then the 2019 floods happened and there was little he could do except move the grain that he could from his storage bins and abandon his farm and home.

Throughout the history of water management, the author tells the stories of individual farmers as well as communities that are impacted by flooding disasters. The author describes that risk reduction for flooding is often on a cost-benefit analysis that does not necessarily always take in the disproportionate impact land ownership and access has on communities within a floodplain. A significant example of this was a 2011 flooding event that impacted Pinhook, Missouri and disproportionally impacted a small community of black farmers. To reduce the risk of flooding in higher density areas, the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway was activated, which meant deliberately breaching a levee in the floodway. According to reports, residents of Pinhook were given very little to no warning or assistance to evacuate.

Through these stories and the policies that led to them, the author concludes with a focus on river geomorphology and argues that no amount of engineering and maintaining the infrastructure approach of the past can keep the river in place and tamed for our functional use. Rather, as the last chapter is titled, we must “retreat and fortify.” Kelley states that the best approach can be learned from nations such as The Netherlands, who take both a resilience and an anticipatory approach to watershed basin management. This takes a new mindset when considering flooding. Kelley states, “… give up something, or lose everything.” (193). An approach such as this involves thinking within a watershed approach for water management and taking in all voices of those within those watershed communities.

Communities can establish a balance between what the water will take and benefits the community may gain through trade-offs that the federal government can broker to protect them. To incentivize leaving land behind, policies could fund community-building assets such as parks and other recreational benefits. Lastly, this approach also means not being afraid to leave places and practices behind. These are things we may have emotional and cultural attachments to, which in the end, letting them go could mitigate the impacts of climate change.